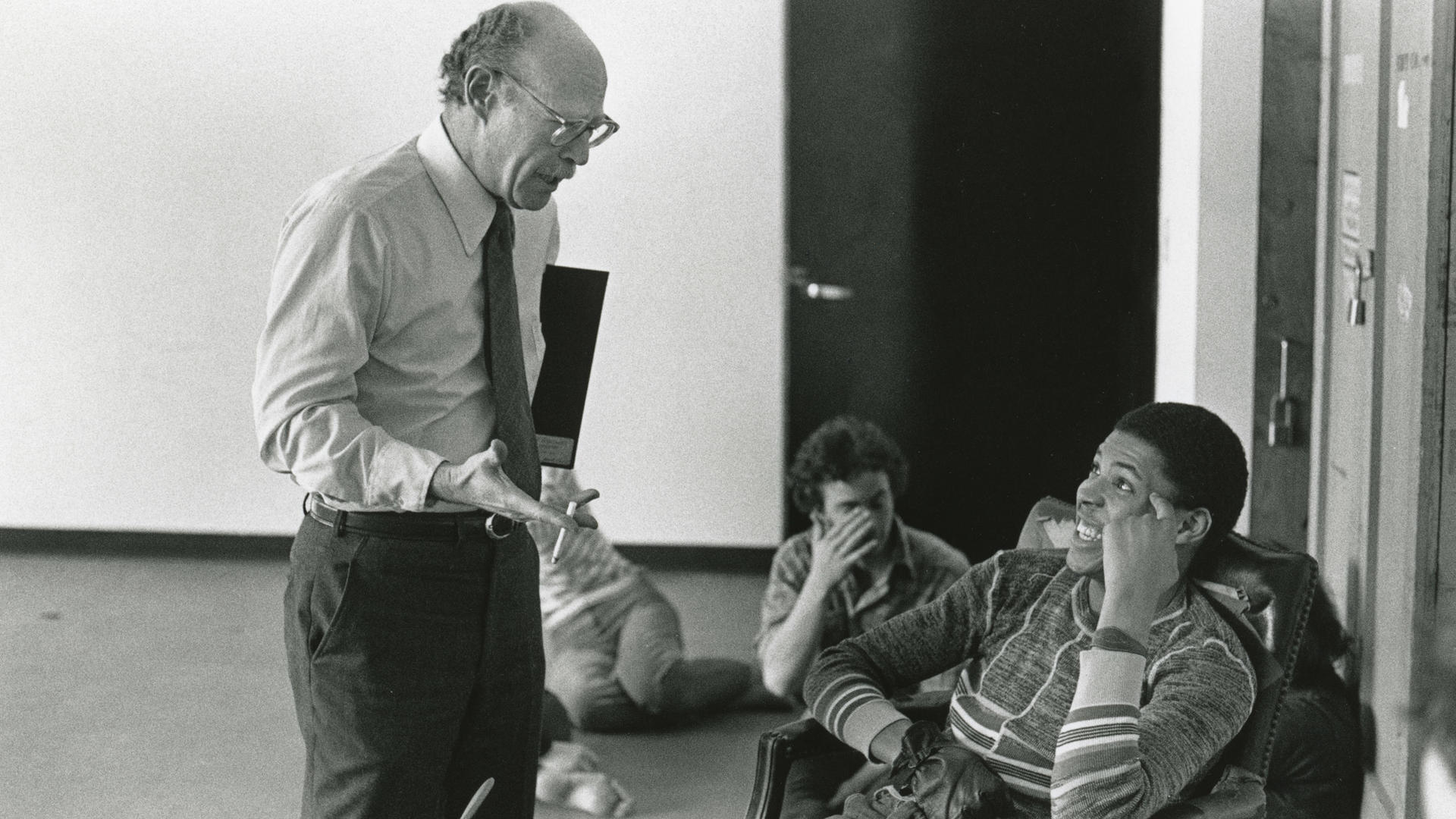

Harold Stone, a Juilliard faculty member and administrator of the Drama Division (1974-2001), died June 10, two months before his 87th birthday. A nephew of the violinist Jascha Heifetz, Stone is survived by his brother, children, stepchildren, cherished friend Linda Amster, and many other family members and friends. His sister, Barbara Gelb, died in February. One of the many Juilliard students he mentored, Bradley Whitford (Group 14), has established a Harold Stone Drama Scholarship. The following is excerpted from a tribute published in The Juilliard Journal in 2001, when Stone retired. It was written by Ralph Zito (Group 14; faculty 1992-2010), who chairs the Syracuse University drama department.

May 2001—Written in black and white, the facts seem simple enough: Harold Stone will retire after 27 years with the Drama Division, the last nine as its administrative director. A quick glance at his biography yields a few more facts: his early career as a stage manager and director, his work with the producer David Merrick. A bit of conversation with colleagues and students might yield some more: specific productions he has directed, classes he has taught, particular insights into the art and craft of acting he has offered over the years. But it would take quite an assemblage of facts to even come close to painting an accurate portrait of the man behind the facts: an administrator of extraordinary skill, a mentor of remarkable wisdom, and a friend of boundless loyalty.

It has been my great privilege to have known and worked with Harold for over 20 years and to have benefited from his unique insights in countless ways. During my junior year at Harvard, Harold—who had been invited back to his alma mater as a guest director—cast me as Horace in Moliere’s School for Wives. During a pre-rehearsal conversation, he offered the words of encouragement that convinced me to pursue a career in the professional theater. After I had expressed doubts about my own ability to succeed as an actor, Harold said, “Well, I think if you work really hard at it, you might be able to do it.” In the years that followed, I would come to recognize and appreciate the clarity, brevity, and understatement of that response as characteristic of Harold’s style.

After college, I spent four years at Juilliard as a student and Harold’s advice guided me—as it has done generations of Juilliard actors—through an incredible array of situations. Some were relatively straightforward: which headshot to choose; whether to cross before, during, or after the line. Some were fraught with complexity: how to constructively express dissatisfaction with a teacher or a class; how to cope both emotionally and financially with my father’s sudden and unexpected death. I particularly remember sitting across from him at his desk one morning in my second year, when I was in quite a state about what I perceived to be the unfairness in the way I had been cast in our final project. Harold calmly endured my tirade, my tears, my questions, my execrations, and my demands. Over the course of the 20 minutes that I sat there (I had skipped my first class and ambushed him on his way into the office), he listened to me, questioned me, admonished me, and ultimately taught me: about myself, about the goals of training, about the business of being an actor. And while all of my negative feelings didn’t evaporate into thin air, I did leave his office feeling that I could cope with and learn from the situation at hand.

As students we knew that Harold’s door was always open. Just as he helped me, I know he helped many of my classmates—and he always did so with grace, strength, and compassion. Multiply the four or five incidents mentioned here times an average of 20 students per Drama Division class, and then multiply that times the number of years Harold has been with the Division; connect the dots, and these accumulated facts bring the portrait into slightly clearer focus.

Where once I was glad to call Harold teacher and friend, I am now also honored to call him colleague and mentor. I find myself making my way to his office just as often as I did during my student years; only now when I park myself at his desk (always piled high with the paper trail of the countless matters it falls to him to oversee), I am waiting for words of wisdom about dealing with a student, not a teacher. Or perhaps seeking some advice about life in general, not life in the theater. Or looking for the answer to “21 across” in today’s crossword puzzle (he’s better at it than anyone I’ve ever known). I might be laughing at one of his characteristically wry observations about life or the decline of clarity in written and spoken English. (I just know he’s going to find at least six grammatical errors in this article, and the only thing that will allow me to endure the humiliation of his having found them is the warmth I will feel as a result of the generosity and clarity with which he will share his observations.)

While the Drama Division is truly fortunate to have Kathy Hood (an administrator of uncommon skill and a woman of apparently limitless energy and commitment) succeed Harold—and while, in turn, she (and we) are equally lucky to have Richard Feldman, a teacher of endless patience, dedication and insight—we will undoubtedly feel the pang of Harold’s departure for quite a while. But we will also feel the reverberations of his presence for years to come. He has left a mark on this institution and on all who have come into contact with him here in ways we can only begin to describe.