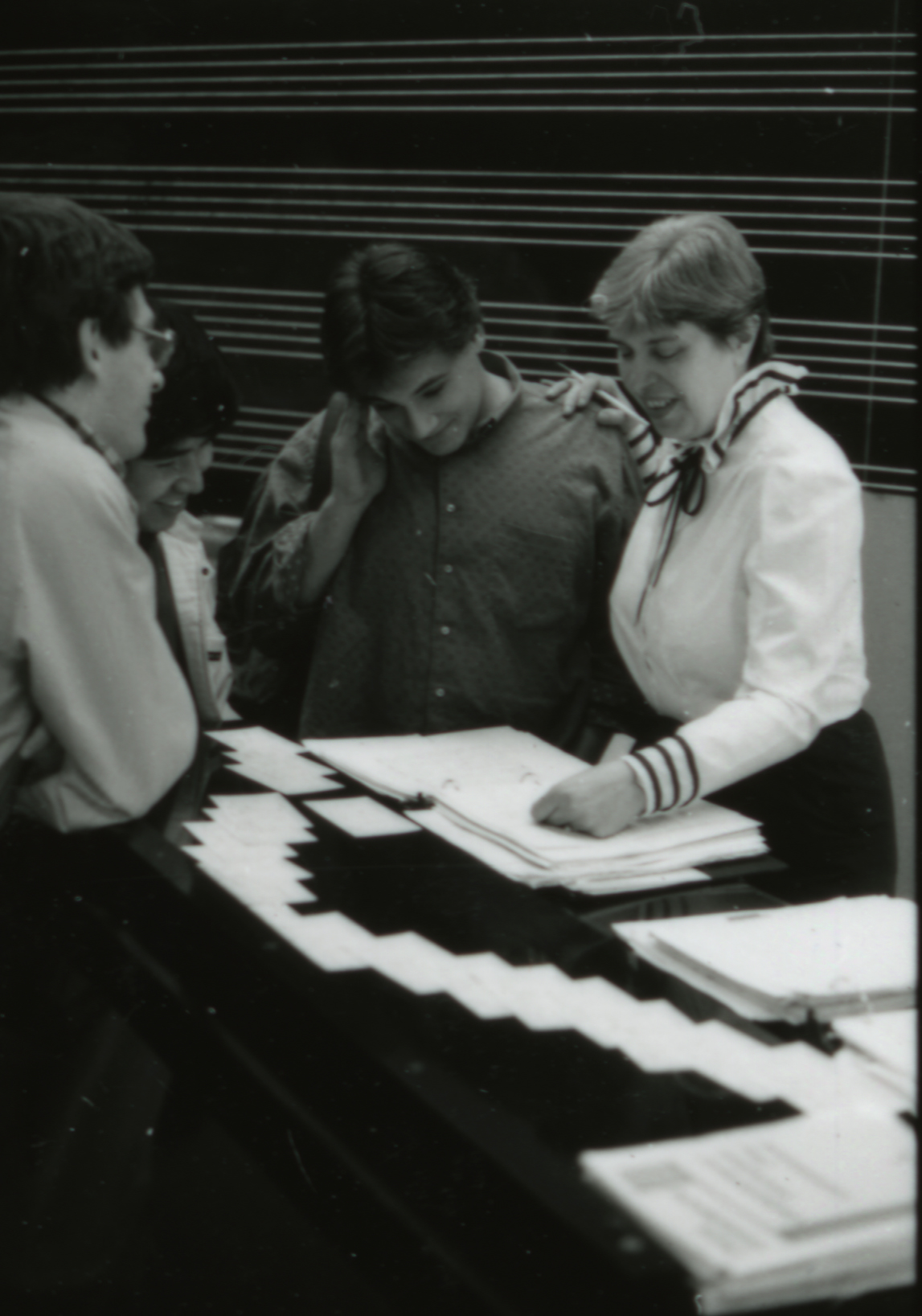

Cox taught generations of musicians using her own ear training curriculum, for which no model existed in the U.S.

When legendary ear training faculty member Mary Anthony Cox (BM ’65, MS ’66, piano; faculty 1964-2013) died January 16 after a long illness, the tributes started pouring in. Ear training is a required class for all Juilliard musicians, and Ms. Cox, as she was always known (after having always been known as Miss Cox) was a most formidable and memorable instructor.

Cox grew up in a musical family in Montgomery, Ala., and by the time she was 12 she had her own piano students. After studying music in France for 10 years, she returned to the U.S. and entered Juilliard as a piano student of Rosina Lhévinne (faculty 1925-76) and Jeaneane Dowis (BS ’53, piano) and before she’d even finished her degrees, she joined the faculty. A few years later, she co-founded the Craftsbury Chamber Players, and after she married local widower Morris Rowell, in 1974, she taught at Juilliard during the week and then flew to Vermont every weekend. Rowell died in 2017; Cox is survived by five stepchildren and many grandchildren, great grandchildren, and other relatives.

When Joseph Polisi presented Cox with a President’s Medal upon her retirement, in 2013, he read the following citation and profoundly thanked her for her dedicated service to the institution and its students and for the indelible impact she had had on the arts.

“In 1964, you were appointed to the ear training faculty at Juilliard, where you developed a program for which there was no existing model in the United States. As a teacher, you were known for your impeccable musicianship, the uncompromising standards to which you held your students, and your ability to bring humor to a subject matter that is perceived by an uninformed few as dry. Employing a gamut of pedagogical techniques ranging from cryptic interlocutions to gentle encouragement to outright ‘psychological warfare,’ as one former student jokingly offered, you not only taught generations of students how to become better musicians, but also taught hundreds of teaching fellows how to teach—and they are enduringly grateful.”

A Tribute to Mary Anthony Cox

by Wayne Oquin

Known as much for her wit as for her exacting standards, Mary Anthony Cox had a classroom presence like no other. When a brave student once raised his hand and asked her why she was so firm, she quipped in her trademark Alabama accent, “Honey, you should have seen me back in 1980; I was hell on wheels.” I met Ms. Cox in the fall of 1999, and it didn’t take long to see that beneath her humor, beyond her strictness, was a compassionate person, a remarkable musician, and an incomparable teacher.

In the late 1940s, Mary Anthony studied in France with the world-renowned Nadia Boulanger at Fontainebleau. How unlikely that a 15-year-old Alabama girl would find herself in Paris, methodically working through hundreds of examples from Théodore Dubois’ Treatise on Harmony with arguably the foremost music teacher of the 20th century. Mary Anthony brought this back to the U.S., and for 50 years taught so rigorously that it is no exaggeration to claim that a portion of a truly great lineage of music pedagogy would not have flourished without her efforts.

In her time at Juilliard Mary Anthony Cox developed a unique and elegant ear-training curriculum, very much her own, so watertight in its comprehensive approach that students would leave her class transformed, able to aurally perceive what had previously been for them impossible. The core of her teaching was rooted in tradition: the connection between performance and intense listening, between recitation and dictation. But her unique exercises and drills gradually leading students to become fluent in intervals, scale degrees, keys, and clefs were hers alone.

Ms. Cox’s classes were exhausting. She had students actively participating the entire time: play and sing, sing and conduct, “ta” and clap. Her command of classroom psychology was formidable. She would introduce a new concept in such a way that it would stick for a lifetime. If a student answered a question incorrectly, she would sing the wrong answer so that the class would immediately hear the mistake.

She had little use for technology. Each fall, invariably some well-meaning freshman would inquire as to why she hadn’t answered his email. “Young man, I am a lady of the 19th century. My acknowledgment of the 20th century is a home cassette recording answering machine. Wait for the beep.”

Musicianship was her passion, but she was more than an ear-training teacher. She taught life skills—the importance of arriving on time, how to prepare, how to focus, how to conquer performance anxiety, and the necessity for nutrition and sleep.

Her legacy lives on at Juilliard in me and my colleagues—Kyle Blaha, Dan Ott, and Rebecca Scott—and we think of her daily. Many of the recitation exercises she created still exist in the rotation of our curriculum.

Reflecting on Mary Anthony’s legacy—her talent, toughness, compassion, humor, and sense of duty—I keep coming back to her sense of fairness. When it came to grading, she was painfully impartial. While she believed anyone could learn with enough hard work, she accepted no excuses, offered no extra credit, and extended no deadlines. The grade given was the grade earned. An 89.9 was a B+; no rounding up. She willingly suffered the consequences of being objective; accepted her lumps on a few negative teaching evaluations. And she read each one religiously.

I’ve delighted in the tributes to Mary Anthony on social media, some from former students who are the first to admit that they did not exactly enjoy her tactics during their student years. I take heart that what Ms. Cox ultimately achieved, among her reputation and many awards, is the near unanimous admiration of her students 10, 20, or even 30 years down the line. She earned it.

Wayne Oquin (MM ’02, DMA ’08, composition) chairs the ear training faculty

Have a Mary Anthony Cox story to share? Let us know at [email protected].