Michael Griffel, chair of the music history department, looks into the musical nuances of Mozart's Don Giovanni, which Juilliard Opera presents April 24-28

Le nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni, an operatic pair brought to life by Mozart and Da Ponte a mere 18 months apart, possess a number of similarities but also significant differences. For instance, Figaro is an affable, good-natured, somewhat bumbling servant in a bright and amusing comedy that nevertheless addresses serious domestic and societal issues. Don Giovanni, on the other hand, is a sensually insatiable, uninhibited, unrepentant, possessive master in a dark, violent, and supernatural drama that is camouflaged by its comedic characters and situations.

Mozart pulls out all the stops in characterizing Don Giovanni the man and Don Giovanni the opera through his inimitable music. Unlike the highly diatonic world of Figaro, Giovanni is awash in chromaticism. The chords that would become the “bread and butter” vocabulary of the 19th century—augmented sixths, Neapolitan sixths, and diminished sevenths—support falling chromatic bass lines, falling sevenths, melodic half-steps, all kinds of diminished intervals, and the fa-mi (F-E) descending Phrygian second. Octave leaps add to the anxiety, tension, and instability of these harmonic and melodic devices, as does the curvature in general of Mozart’s melodies in this dramma giocoso. The palpable rising and falling melodic motion in the opera seems to correlate with other antonymous pairings in this opera, such as life and death, decorum and chaos, master and servant, attraction and repulsion, and comedy and tragedy.

The action in Don Giovanni moves quickly. The kaleidoscope of characters, each with an intriguing storyline, demands this. Mozart manages to make the audience care about Don Giovanni, Donna Anna, Don Ottavio, Donna Elvira, Zerlina, Masetto, Leporello, and—oh, yes—the Stone Guest (aka the Commendatore). Every one of them has stirring solo and ensemble numbers, and each is drawn into the nefarious web that Don Giovanni spins. Really, only the Commendatore, as supernatural a power as Don Giovanni, can stand up to him and bring the miscreant down in the opera’s finale. The D-Minor tonic of the opening of the overture, which gives way to a D-Major continuation in sonata form, returns to dominate and darken the opening and final scenes of the opera. Between these moments of violence, vengeance, and destruction in D Minor, Mozart composes fourteen arias, five duets, two trios, one quartet, and one sextet, all in major keys.

Mozartean subtleties abound in this masterpiece. For example, in Donna Elvira’s great aria in Act II, “Mi tradì,” she tells the audience that although Don Giovanni has betrayed her and vengeance should be hers, she pities him and fears for his life. In the second episode of this rondoesque aria in E-flat Major, the music turns to E-flat Minor for Elvira’s coalescence of revenge and worry. The orchestra introduces this episode with the motive of the falling fourth harmonized by tonic and dominant chords, copying the melodic-harmonic motive of the start of the opera’s overture.

Here the passage is a minor second higher, that is, a Phrygian second higher, and the Phrygian is promising us that what Elvira fears is what we all know—that Don Giovanni is doomed. He is, in fact, Il dissoluto punito (which means The Rake Punished and is part of the full Italian title of the opera)!

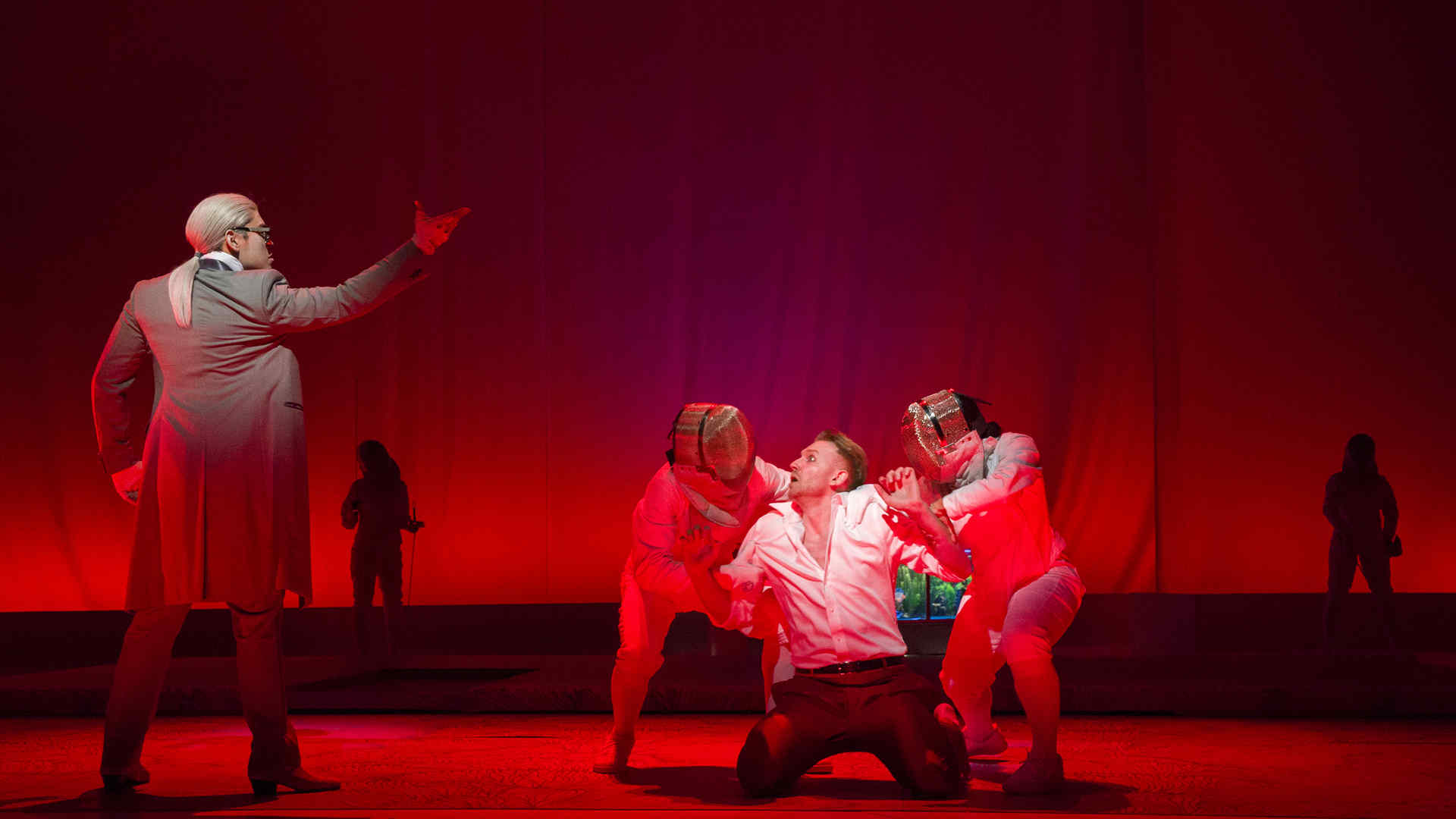

As an example of dark comedy, in Act I, Leporello, attempting to console Elvira, who does not quite understand that Don Giovanni is not the marrying kind, tells her not to take her situation so personally because Don Giovanni has courted not 1, not 10, not 100, not 1,000, but 2,065 women! Audiences may laugh at this attempt to mollify Elvira, but the truth of the matter is that Giovanni is not simply a man but, rather, a demon, a serial seducer and possessor of women. Mozart shows him “possessing” the opera’s three women musically by having him sing in the style of whichever one he is with at the moment and by inserting some of his motivic material into the music that they sing. The mythical Don Giovanni is ultimately brought down by the opera’s only other mythical power, the Stone Guest, who extinguishes Don Giovanni’s hunger through the only way possible: death. Released from Don Giovanni’s spell, the rest of the characters turn into a troupe of opera buffa inhabitants, celebrating mainly in major tonalities, consonant harmonies, clear rhythms, and even a brief touch of fugal exhibitionism, as they send themselves and the audience home in the best of spirits.

L. Michael Griffel (MS ’66, piano) is the chair of the music history department