What would happen if you were one of the two last people on earth? That scenario—bandied about by Igor Stravinsky and Dylan Thomas in the 1950s—is the premise for Oroborium, Graduate Studies faculty member Jonathan Dawe’s (MM ’91, DMA ’95, composition) latest work, which will be premiered by the New Juilliard Ensemble on April 28. Piano master’s student Jie Fang interviewed Dawe about his work.

What is the creative origin of Oroborium?

Jonathan Dawe: I had been intrigued by Stravinsky’s never-realized opera project with the great Welsh poet Dylan Thomas for a long time. Stravinsky and Thomas met each other in 1952 and began exchanging ideas about creating an opera together. Their idea was to depict the devastation of earth by some cataclysmic event. A man and woman would be the only survivors, from earth or perhaps even extra-terrestrial. They would have no memories and thus would have to re-invent language amidst the new fantastic landscape around them. Unfortunately, the project never materialized due to Thomas’ untimely death a year later.

So what’s your take on it?

JD: Terry Marks-Tarlow, the librettist, and I imagined that a creation myth, or a re-creation myth, could serve as much as an inner tale as an outer one about the evolution of human consciousness. The title, Oroborium, derives from the Ouroboros, the mythological snake that symbolizes self-creation and renewal.

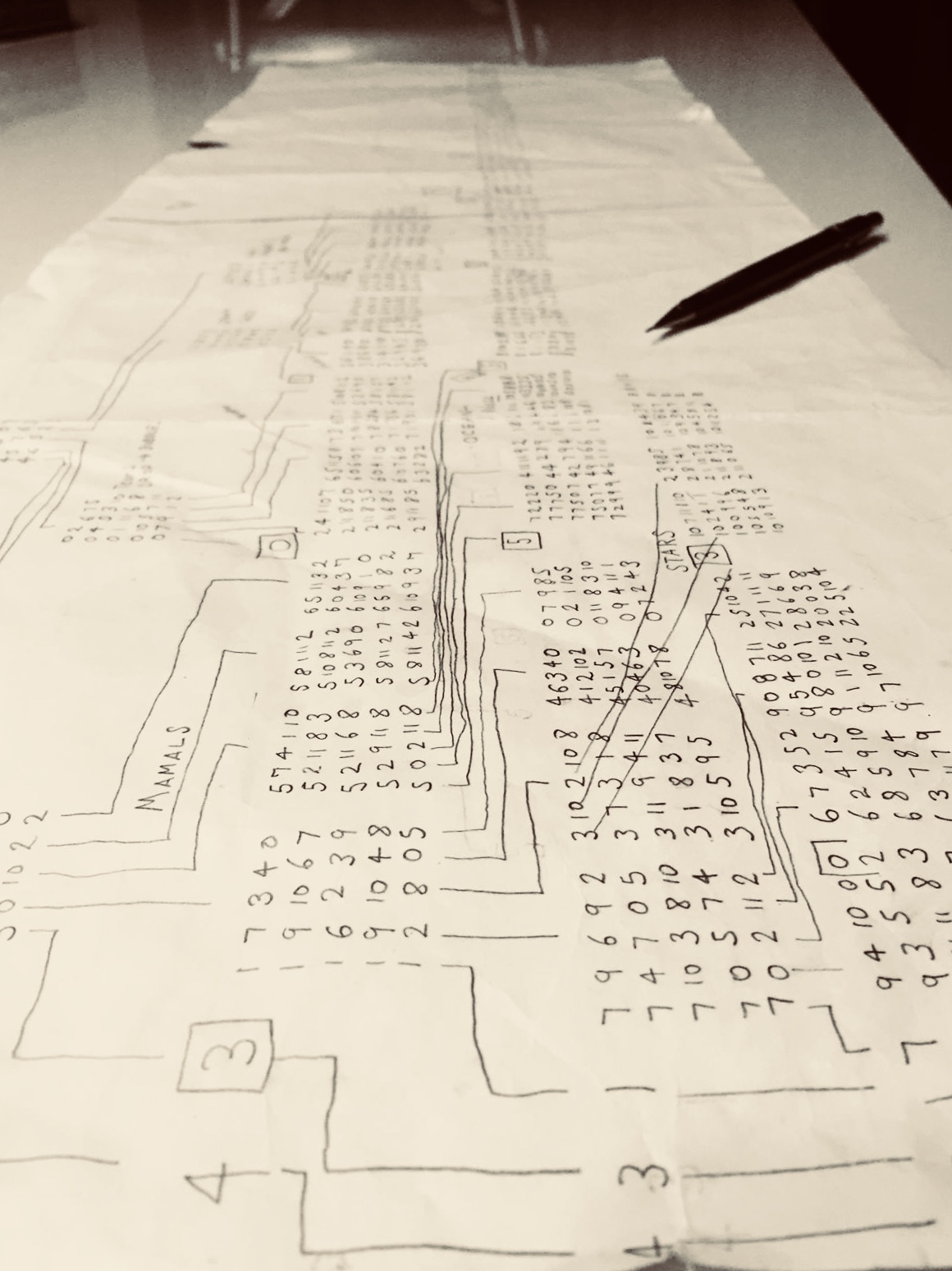

Every note and the entire musical texture, from beginning to end, is derived from the growth of the original five-note row that Stravinsky used in his In memoriam Dylan Thomas (1954.) From those five pitches, using Stravinsky’s own technique of “rotational arrays,” hundreds of generations of pitches are grown; this leads to all kinds of interesting harmonies down the road that don’t sound anything like the original Dylan Thomas motif (see illustration).

I understand that one of your own compositional techniques of extracting one small part of an earlier composer’s music and then generating an entirely new composition around that fragment is a type of musical “fractal” process. Could you elaborate on what exactly is a fractal?

JD: It can mean a lot of different things. In this context, it means that a small shape is grown in particular ways so that its larger result not only reveals a bigger form of itself but that its very growing structure is a result of nested self-similar bits of itself. So it’s a type of recursive idea where the shape is manifest within itself, with numerous scalings of itself embedded within its growing structure. In this piece, I apply different fractal operations for each scene, the final being projection on the overtone series.

I’m curious about how your librettist, Terry Marks-Tarlow, who is a clinical psychologist in Santa Monica found common ground with your music?

JD: Terry is unique in that. She uses fractal geometry and related concepts in her work as a clinical psychologist. She is also a visual artist and a writer. I love working with her and find her words so sonically sensitive and powerfully meaningful.

Piano master’s student Jie Fang (BM ’15) holds Rosalind Carter and Isabel Mason scholarships

Also on the bill in this concert, NJE founder and conductor Joel Sachs tells us, are the “New York premiere of Salvatore Sciarrino’s evanescent Fanofanìa followed by the U.S. premiere of Costa Rican composer-guitarist Alejandro Cardona’s decidedly non-evanescent Sweet Tijuana,” which is based on Mexican narcocorridos—songs composed in homage to (or fear of) drug warlords. We’ll also perform Icelandic composer and flutist Kolbeinn Bjarnason’s After all, the sky flashes, the great sea yearns, which he wrote for NJE.” Read the program notes here.