A few weeks before commencement, the Drama Division gathered to witness a reading of playwriting fellow Tearrance Chisholm’s How Not to Write a Slave Play, which had emerged from a commission for Georgetown University. In 1838, the struggling Georgetown sold 272 enslaved peoples it owned to help pay its debts and keep it afloat. In 2016, after protests brought that transaction to light, Georgetown’s Laboratory for Global Performance and Politics commissioned Chisholm to address the issue in a more contemporary context. Hayward Leach, who was winding up his second year as an acting student, wrote about the experience of being in How Not to Write a Slave Play, and he also corresponded with Chisholm over the summer about the experience of writing it and watching it take shape on stage.

Twenty-eight black actors. One play. Twenty-eight black actors. Five tables sprung open, half the length of the room. Twenty-eight black actors. All of the black students in the 2017-2018 Drama Division. Twenty-eight. That number stayed in my head throughout the May evening when we performed How Not to Write a Slave Play—more of a sensation than a number, really. A sense of what could be. A sense of wonder. A sense of “how is this going to work?” Grand anticipation.

How Not to Write a Slave Play follows a group of actors, called The Symphony, reading a play written by Mallory Maelstrom (played by Mallori Johnson, Group 50), about the history of slavery at Fillintheblank University. Over the course of the play, the actors become increasingly vocal, and they commandeer the construction of the play, ultimately wresting it from Mallory’s control. All actors play characters with their first name. The play takes place around a table. Meta to the max.

Tearrance subsequently told me it hadn’t been easy to figure out how to start writing. “Having such a real and current issue to discuss dramatically is a huge responsibility. I was stuck, but then I got the idea to write for the entire black acting body of Juilliard and that’s when things started happening. It seemed like the perfect way to honor the 272 by simultaneously honoring the 28 black actors in another academic institution. And it served as a way to unpack my feelings about slavery on stage and what is the role of black folks as citizens and artists.”

From our initial rehearsal three days before the reading, we could feel the electricity coursing around the table. Before we read, Tearrance told us, “Anything you do is right. There are no mistakes.” It was if he had opened a window. I had heard similar direction before, but in this context, playing a character named Hayward in an all-black cast, I heard Tearrance reaffirming my inherent humanity. I heard him telling Hayward the person: “Whatever you do is right. However you exist is right.” And I would have been happy just doing the reading like that, for us. But the play was built to be shared.

When we sat down for the reading/performance, we immediately felt the impact of having an audience. Aside from a few friends Tearrance invited, the audience was demographically mostly white.

Jarrett (played by Jarrett Desean, Group 50), addresses this fact, asking if he and the other actors can scrap the meta theater idea:

Jarrett: Can this be real? Like it’s just us. In a room. And no one’s watching.

After consideration, Mallory and the cast decide to ignore the audience.

Mallory: Great. Progress. This is not a play about a play. This is us. And we’re real. And there’s a wall there, there, there, and there. No audience. We’re not performing for anyone other than ourselves.

I found myself thinking, as I often do, about the negotiation of the black actor, or any actor of color. Yes, I think, I want to share unheard, culturally specific stories and to voice the songs of ancestors buried under the landfill of reductive and repetitive storytelling. At the same time, I don’t want to demote acting to cultural demonstration and feel like a trick pony. Having an audience, ironically, sometimes feels more invasive than constructive. What does it mean to perform blackness? What does it mean to get on the stage and say, “this is the black play”? What, then, is the relationship to the audience? Can you truly effectively forget the audience and build community? These are the precise questions Tearrance’s characters wrestle with in How Not to Write a Slave Play.

By the end of our reading/performance/not performance, the actors have completely deconstructed Mallory’s piece. The Furies, played by Jayme Lawson (Group 48), Jules Latimer (Group 49), and Elijah Jones (Group 50), address the audience directly:

Elijah/Fury 1: Dear White GAZE. G-A-Z-E. We are the Furies and this foreword is the only part of the play that is specifically for you. Because this play is specifically not for you. However we have been magnanimous enough to let you come.

Jayme/Fayme/Fury 2: Cause we can't exactly keep you out.

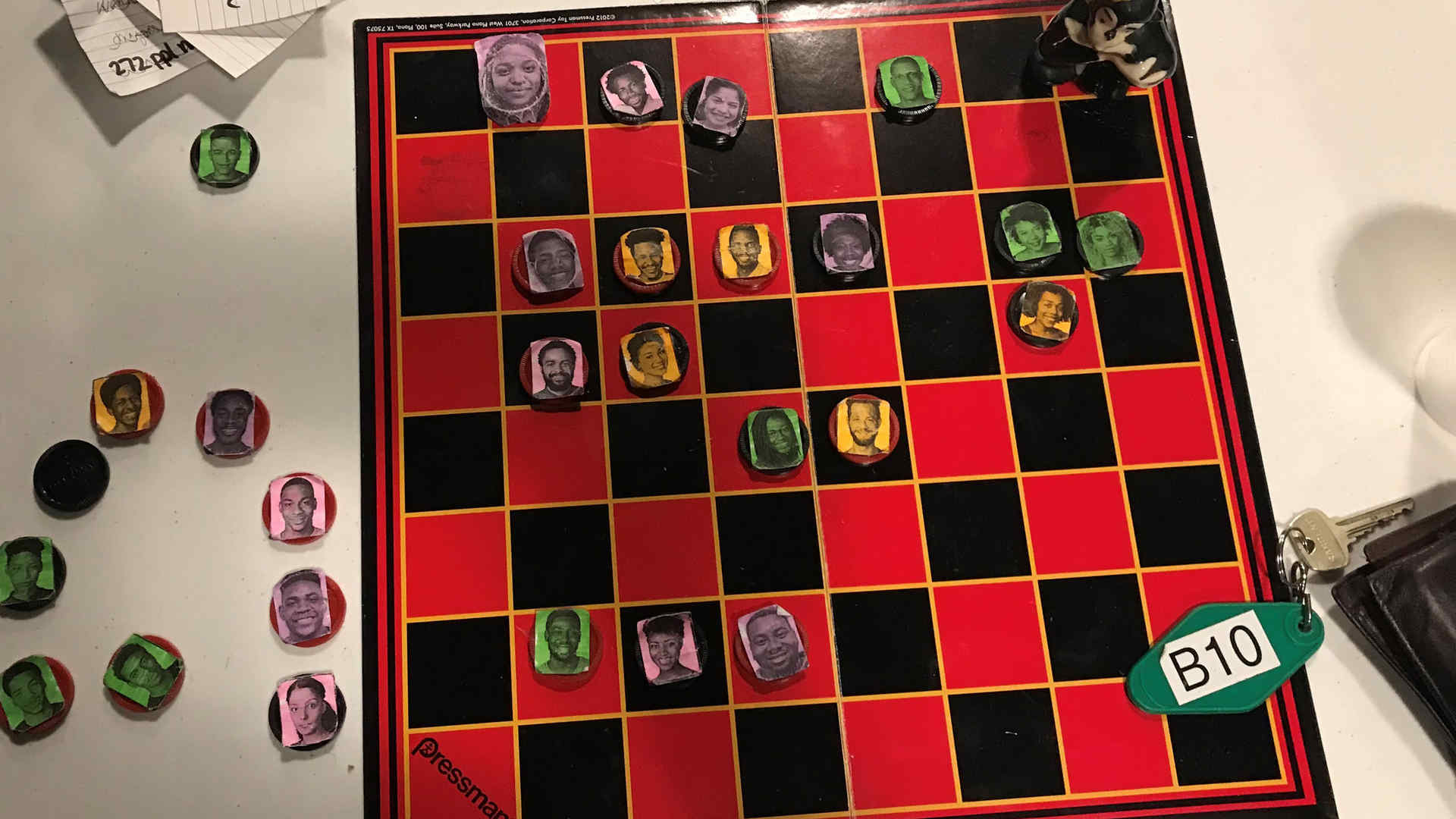

When we corresponded over the summer, Tearrance told me more about the process of writing How Not to Write a Slave Play. “As I wrote the play, I pasted all the actors’ headshots on checkers, and I took them everywhere with me: San Francisco, Cleveland, Toronto, St. Louis, London. So when I finally actually got to see them all in the room it was sorta overwhelming, but ultimately the reading was truly edifying.”

As for the rest of us, Tearrance’s play sparked many conversations, and I’m sure it will continue to fuel explorations of blackness in theater. For now, I’m just grateful to count myself among the twenty-eight.

Third-year drama student Hayward Leach performed as part of the non-Equity company in the Williamstown Theatre Festival this summer