Chaos and Order

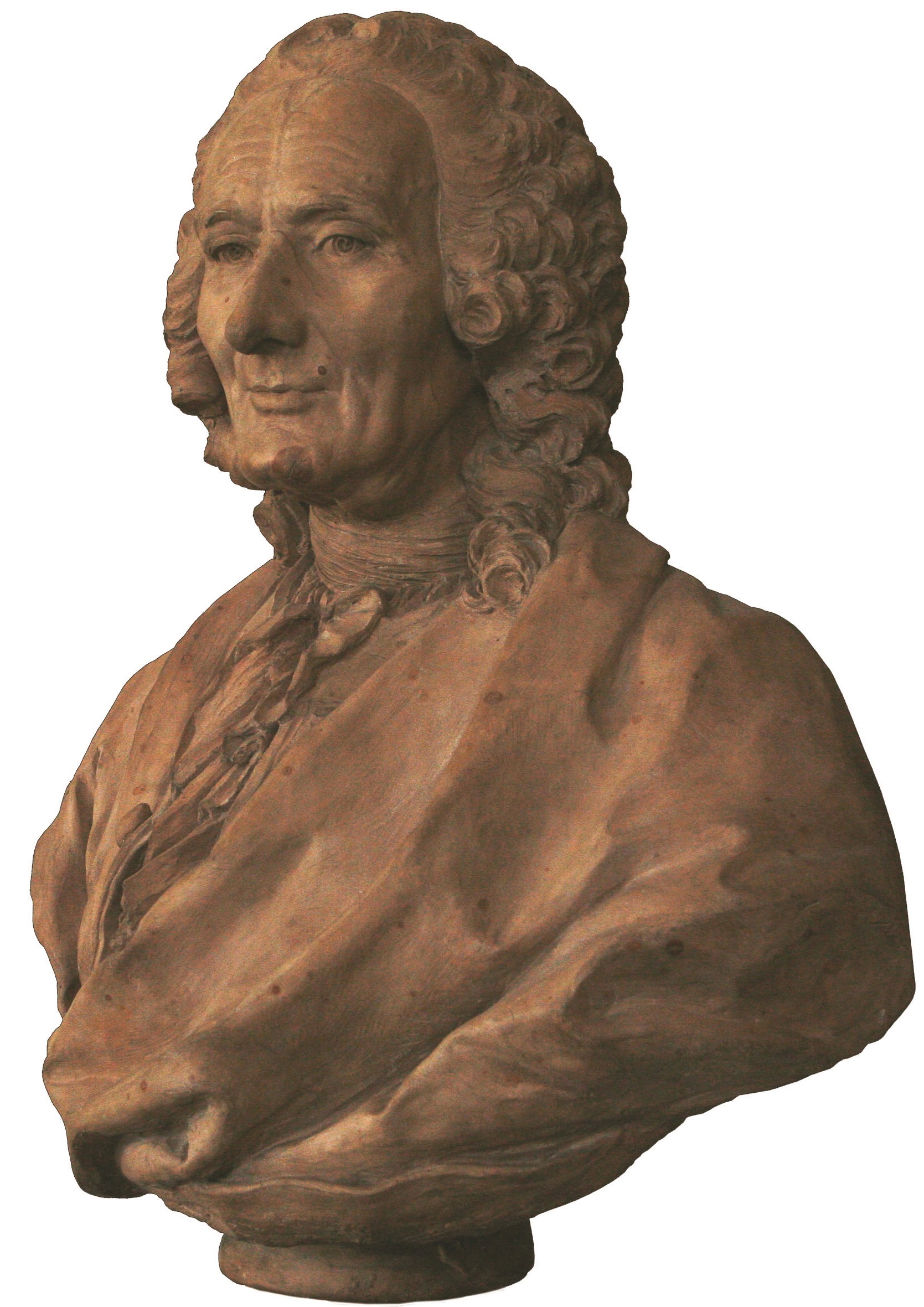

Over a lifetime of making music, Jean-Philippe Rameau remains one of my absolute favorite composers, both to play and to listen to. A lot of us tend to think of the music of Bach and Handel and Vivaldi when we hear Baroque music, but for me the sheer kinetic energy of Rameau makes him one of the most vivid dance composers before Stravinsky. His rhythms are compelling and propulsive, and his orchestrations are hugely inventive. Rameau has an iridescent sense of instrumental color that I think of as particularly French, a trait you can trace down through Berlioz and Ravel to Boulez and Gérard Grisey. And he shares a love for the keening, plaintive sound of the bassoon in its upper register with Stravinsky; you could think of some of Rameau’s dance music as a Sacre du printemps for the 18th century.

By now the Juilliard community is well aware of the power and spectacle of Rameau’s dramatic writing, after our collaboration with Vocal Arts last spring on his groundbreaking first opera, Hippolyte et Aricie. That devastating portrait of obsessive love is still on view outside Juilliard, with the amazing photograph next to the building’s main entrance of mezzo Natalia Kutateladze in a stunning red dress as the haunted Phèdre. But since big French tragedies take a good long time to unfold, we had to cut a lot of the dance music from Rameau’s score to allow the drama to breathe.

This October, I wanted to try a different kind of collaboration, this one with the Dance Division. I’ve created four suites of dances out of some of the greatest moments in Rameau’s operas, and we’re putting them in the talented hands (and feet!) of several student choreographers: fourth-years Moscelyne Parke-Harrison, Maddie Hanson, and Ethan Colangelo. Each choreographer is working with five classmates to create their own story of what Rameau’s music says to them—and I’m happy to say that I have no idea what they’ll come up with!

You could think of some of Rameau’s dance music as a Sacre du printemps for the 18th century.

The music I’ve given our choreographers includes some of Rameau’s delicate and melancholy slow dances—pensive sarabandes and air tendres—as well as boisterous contredanses, gavottes, tambourins, and rigaudons. I’ve chosen one of Rameau’s rarely heard overtures to open each dance suite. Rameau had a particular gift for creating vividly theatrical overtures, and they’re among the most striking soundscapes of the time.

We begin our program with the overture to Zaïs, a portrait of chaos (represented by a muffled, pitchless drum played fortissimo) eventually giving way to order. The concert also includes Rameau’s ferocious overture to Zoroastre, full of jagged rhythms and abrupt silences, and his sensational overture to Naïs (I know, he didn’t get the best opera titles), which depicts a massive battle on Mount Olympus between the Gods and the Titans, and features some truly headbanging syncopations.

No Rameau suite would be complete without some of his great chaconnes, those endlessly inventive forms that spin out over a recurring harmonic framework. I’ve chosen to end each half of the program with a favorite one: the final chaconne from Castor et Pollux, where the orchestra vanishes into thin air, and the heartbreaking conclusion to Dardanus, which features a recurring melody that is one of the most touching moments in French Baroque music.

I’m completely delighted that the Dance Division choreographers are taking this music on as their own, and I can’t wait to see (and hear) the results. As an 18th-century dancing master said, Rameau teaches us all how to dance, players and choreographers alike.

Robert Mealy is the director of Historical Performance