Cellist Aldo Parisot (Juilliard faculty 1988-2003) died December 29, two months after his 100th birthday. He had retired in June from Yale, where he started teaching in 1958. Born and raised in Brazil, he started studying cello at age 7—his main teacher was his stepfather, Tomazzo Babini—and made his professional debut at 12, the start of a long and illustrious performing career. Parisot is survived by his wife, three sons, six grandchildren, and a half brother. Several of his students—formal and informal—paid tribute to their teacher.

By Jesús Castro-Balbi

Here are some of my fondest memories of Mr. Parisot:

- His unbound generosity, humanity, humor, and charisma.

- How much he believed in each student’s own voice, on the instrument as in life, and how proudly he spoke of their accomplishments.

- Seeing how he greeted both the powerful and the indigent.

- How he made sure students had enough to eat and pay rent.

- Great stories over dinner near Times Square (Brazilian food), in Koreatown, and at Cafe Fiorello.

- How he always knew just the questions and the words I needed to hear, and how he reminded me to listen to my wife, Gloria, because she is always right.

- Playing the Bachianas under his baton (actually a Montblanc pen). And:

- “Play closer to the bridge.”

- “Exaggerate the dynamics.”

- “Free your imagination; play with colors.”

Mr. Parisot’s love and legacy live on through generations of friends and students around the world.

Jesús Castro-Balbi (DMA ’04) studied with Aldo Parisot at Yale and Juilliard and is a professor at Texas Christian University

By Clara Kim

I studied with Aldo Parisot from about 1990 to 1996, both at Juilliard and at Yale. He was a very passionate teacher who required nothing less than excellence from himself and his students, and I learned about discipline in his studio. Throughout the years, I would ask him if he ever got tired of teaching, and I can still remember him saying, “never!”

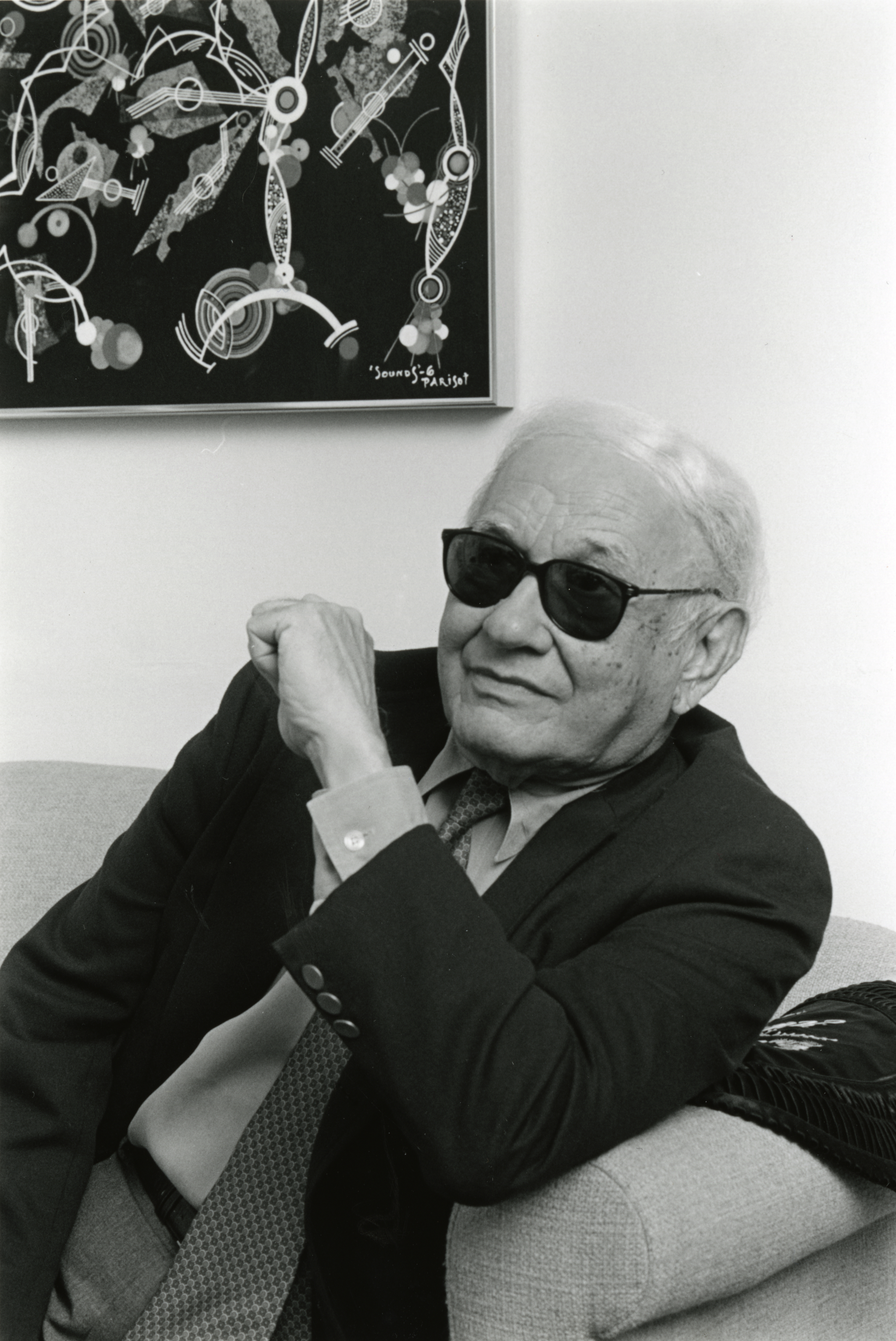

I remember vividly when I played for him for the first time. It was in the middle of the day, yet his studio was dark, with no lights and thick curtains all closed. He had an eye condition, so he wore dark sunglasses all the time. He was smoking and there was a tiny lamp by the music stand for students to see their music. I was 15 years old and scared out of my mind. However, after I played, he started talking, and what he said was very thorough with details but left me with no sense of intimidation.

Although he could be blunt (both in public master classes and in private lessons), he was warm and had a compassionate side, which would pop up unexpectedly. His explanations about the physicality of playing the instrument were always concise and practical. It was a prescription and it worked. He also emphasized and valued the musical individuality and personality of each student.

One of the many things that still stays with me is how he always said we should play the cello as if it were the last time we would ever get to play. As a young musician, this made such an impact on my head and heart—without him, I would not have the cellistic knowledge that I have today, which I use every day, whether I’m teaching or performing.

After many years, I saw him several months ago. He had lost a lot of weight and had become so much softer, but he was still giving advice. I cannot believe he is no longer with us. His warmth and teachings will forever stay in me.

Clara Kim (Pre-College ’92) is on the faculty

By Joel Krosnick

I probably first met Aldo Parisot in 1948, when I was 7 years old. Aldo was the first person I ever heard play the cello. He was for me a gracious person who loved the cello, who played it so easily, and who loved playing chamber music with my pediatrician/violinist father (who became the doctor for his sons). When I was 8, and was asked what instrument I wanted to play, my answer was, “I want to play whatever it is that Aldo plays.”

As I began studying, Aldo came to my room when he heard me practicing, saying, “Play for me, Jô,” and offering many suggestions about the alignment of my body, arms, and hands. I played for him whenever I had something ready to play. It scared me to do that, but Aldo was always encouraging and full of ideas about how to play the music and the cello.

Aldo Parisot was my hero. He was always very serious about his own playing and artistry; I watched him practice for many hours, studying his quick hands and the precision of the angles of his hands and arms as they moved over the cello. While I was "a bit too young" to hear his New York debut, in Town Hall, I did slightly later hear him play Tchaikovsky Rococo Variations and Schumann, Villa-Lobos, Haydn, Dvořák, and Hindemith Concertos with the New York Philharmonic in Lewisohn Stadium, Carnegie Hall, and Avery Fisher Hall. I also heard numerous recitals in New York, New Haven, and Norfolk (Connecticut) among other places.

Once, after I was already active in the profession, I heard Aldo play a recital in Alice Tully Hall, after not having heard him play in some years. To my considerable emotion, it was as magical as ever; beautifully focused sound and astonishingly brilliant hands and fingers. It was not only equal to, but beyond my youthful memories.

It was at that time, when I was in my mid-20s, that I complained to the great cellist Aldo Parisot that I felt as though I could no longer move as quickly and easily around the cello as I had. After assuring me, “The problem is in your head,” Aldo sat patiently in the kitchen of his Guilford home, watched and listened for 20 minutes as I played “everything fast” for him. He then made the precise physical suggestion that made an enormous difference then and has ever since: “Jô, don't stop your hand. Yes, play the notes, but don't stop your hand.” When I did as he suggested, even that night, I became a much quicker cellist.

Somewhat after I joined the Juilliard Quartet (1974), Aldo joined the Juilliard faculty (1988), and taught many fortunate students. In jury exam after jury exam, with his students playing brilliantly, I was able to see more clearly Aldo’s ideas; and the students (it seemed to me) could fly over the cello. He smiled, he was charming, but he had really specific and powerful ideas about how to use the body and hands to play the cello as well as to produce the pure sound he loved, but always sung in the students' own voices. And he would do everything he could do to share those ideas with anyone who had the discipline to really work on them.

When I remarked to him less than a year ago that the speed and elegance of his playing on a couple of YouTube performances were breathtaking, he mildly commented that, “Yes, I had quite a good facility, Jô.” I invite any of us to listen to his recordings of the Villa-Lobos and Guarneri concertos, the Kodály and Graziani sonatas, or the Weber Rondo, and hear the “quite good facility” of the great cellist, my hero, Aldo Parisot.

Joel Krosnick is the chair of the cello department