Have you ever taken one of those online quizzes that tells you things about yourself?

“Which Jane Austen character are you?”

or

“Which kitchen utensil most perfectly encapsulates your personality?” (I am a ladle.)

As I fall victim not only to the flat-brained seduction of such navel-gazing inactivities, but also to the phony snobbery of “more scientific” alternatives, last night I found myself 20 minutes into a rigorous internet self-examination: a quiz filtering me into the slices of a “Big Five” pie chart.

In the results, secreted among the big categories of openness, agreeableness, and neuroticism, lay an innocuous trait that seemed to me to hold the key to all the others—a trait without which it didn’t matter how conscientious, extroverted, or imaginative you were.

Churchill said “Without courage all other virtues lose their meaning.” If you are too afraid to do the right thing, it doesn’t much matter whether you want to or not. But the trait on the quiz is even more all-encompassing than that. What if you are brave enough, but just don’t do it?

The trait in question is Self-Efficacy. “Self-efficacy describes confidence in one’s ability to accomplish things. Low scorers may have a sense that they are not in control of their lives.” So the quiz describes it. I have so many questions.

It never seemed fair to me that someone with the best of intentions, but too uncourageous to act them out, ends up in the same place as someone with no good intentions at all. Why lock all other goodnesses in a chest with the key of courage? Isn’t courage just another trait, unevenly possessed by good and bad alike? And how many benevolent and malevolent geniuses have slipped through life unnoticed for lack of self-efficacy? And what does this have to do with Juilliard?

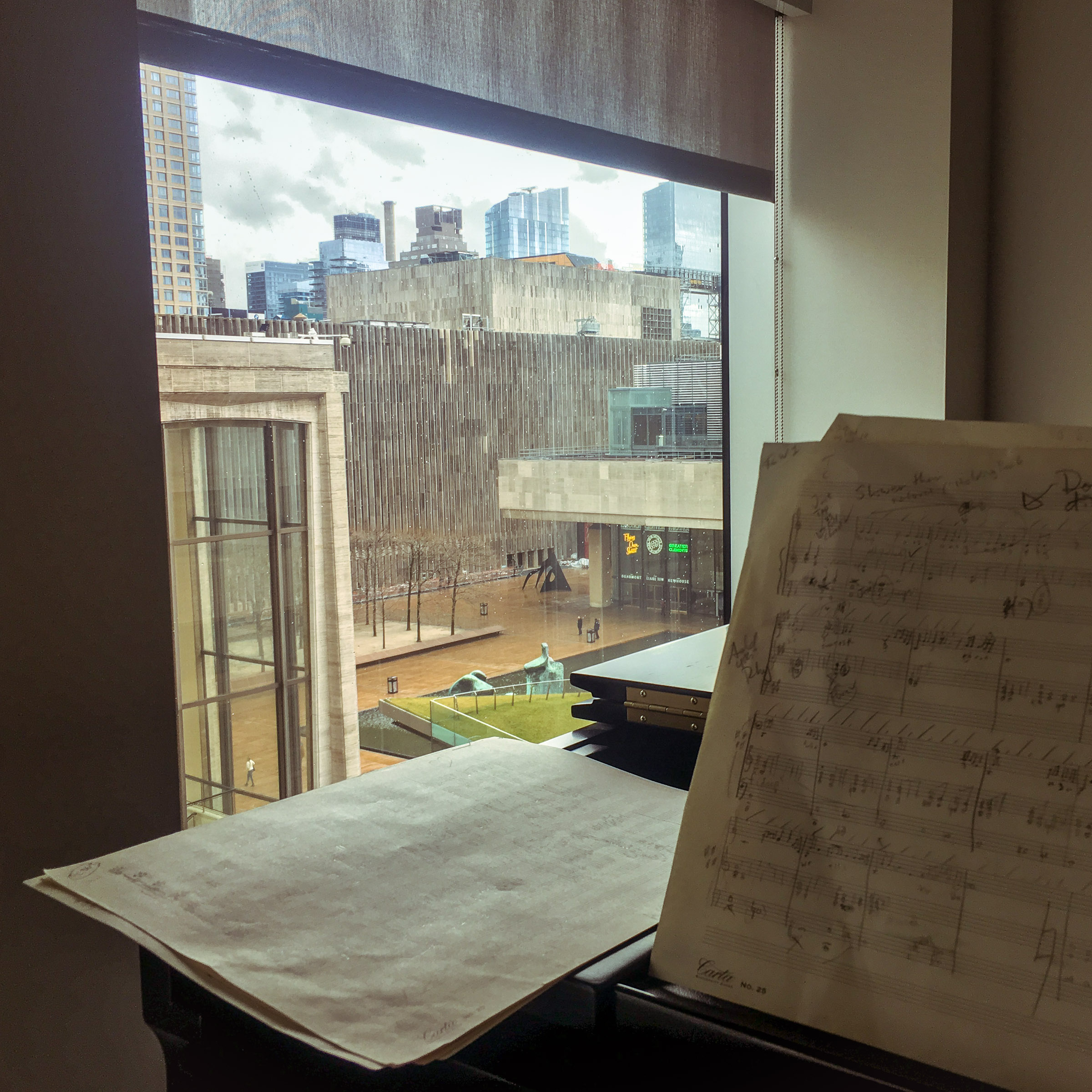

Juilliard is a place of becoming. The clay of talents and bodies and ideas comes to be molded and grown and, crucially, incarnated. None of it matters until it is manifest. And perhaps this prerequisite nature of incarnation is not so unfair after all. It’s a central underlying myth for much of Western thought: The Word becoming flesh and dwelling among us (God scoring high on self-efficacy). At Juilliard, in cascading incarnations, the words become plays, the plays become the speech and movement of actors and designers, these become a production, and the production probably undergoes further incarnations—as impressions in the minds of audiences? As pieces of history? As Wikipedia articles? I’m not sure. And all the while the actors are becoming, well, actors.

Perhaps this incarnation is the only moral choice we make. We all have predispositions, but to take one step in any direction from these predispositions and become a traveler in the incarnate world—a marble that can touch and redirect other marbles—I have always had the feeling that this is the only thing that really matters (which is no skin off the back of ideas, or thoughts, which are the seeds of incarnations, but they must cross the threshold and break through the soil).

I want to become many things at Juilliard. But perhaps what I want most is to become someone better at becoming. To become someone who changes. Someone who puts musical possibilities more quickly to paper and to performance. Someone who always speaks the good they have to say, and does the good they have to do. Someone with fewer plans and more projects. Someone with a great courage to cross the metaphysical boundary of incarnation.

I’ll post an update once I’ve figured out how to do it.

Attend a student performance on campus.