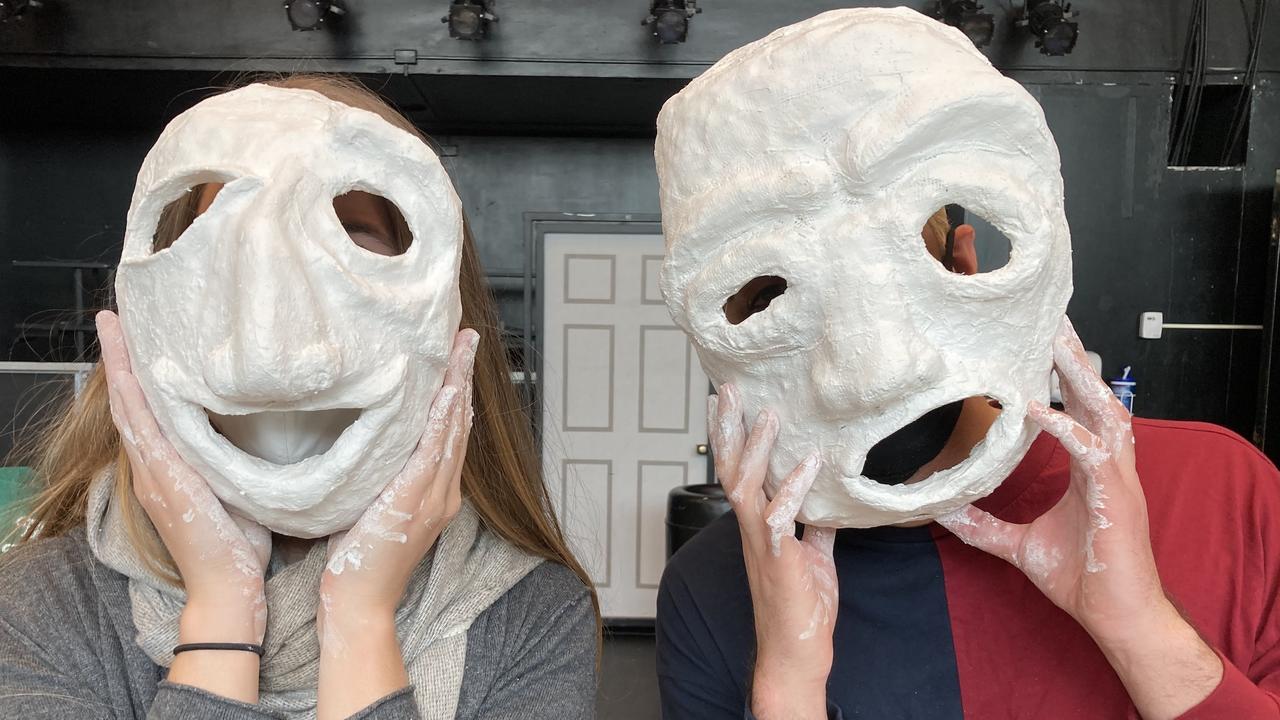

Second-year drama’s mask-making workshop

This spring, at a time when so much of our lives is remote, some second-year drama students were able to have a hands-on experience. Kathleen McNenny’s Self to Character II class participated in a mask-making workshop, and student Cornelius McMoyler wrote about how his mask ended up having a surprising connection to a subsequent performance.

By Cornelius McMoyler

I didn’t know, but the mask did.

I began making it with the goal of forming a skull. That was it. Our teacher had secured stacks of newspaper and tape. We crumpled up the pieces of paper and roughly stuck them to each other until crude clumps became circles became ovals became something of a head. Human? Who knows. We were then encouraged to add additional clumps to form “features”: a bulbous nose, smacky lips, fleeksome eyebrows. I was in a funny mood that morning: hazy, open, doomed, curious. I made some decent ridges for eye sockets, two long wormy lips that I figured would look better later. Some part of my brain that thankfully escaped my years of psychoanalysis started to make a hump on the forehead—it was not consciously directed, but rather curious: Follow the hump, give the hump a home. Is it a wound? Maybe it’s a big bonk, like when a Looney Tunes character hits their head and a red silo of irritation rises out of their flesh.

I spent a long time on my bonk; when we were supposed to move on to applying a wet imitation-papier-mâché to harden and finalize our features, I was still bonking. Don’t worry, don’t worry about the speed of things, you’re not at a driver’s license test and there’s no detention, the point is to discover what this is: Follow the bonk. I added more and more layers of newspaper to it—flat bits, crumpled bits, crumpled-torn-in-half bits—but it still appeared unrecognizaable next to the size of the face and eye sockets. Mmm, no. This would have to stand out clearly and proudly to anybody looking at it as a Big Bonk. Finally, layers and layers later, it looked phat and moundlike and certainly like somebody’s problem, a bonk that was very much alive and in pain or grief. A solid 15 minutes after everyone else I began wetting and applying the paper. As I covered it in thick yogurty strips, smoothing out wrinkles like a nurse, I admired the burgeoning quality of this face: two vacant eyes and a wide mouth with a visible, needy bonk. *He* appeared lost, hurt, and wondering. This inspired me to let him moan, or creak, or drool, so I pulled those lips apart and curled them into some kind of exclamation: “ohhh no” “whooowowou are you?” “whatuwawawata am I gonna do?” By the end of class, my hands and forearms fully yogurt-zoned, I had no idea what *he* was, but I felt that he had something to say—he wanted something—and that was good.

Through the next couple classes, we ended up hardening and painting our masks, lastly punching holes in their temples and threading through elastic headbands and trying them on. We were encouraged to stand in front of the mirrors and find the “shapes” that our masks asked for. Staring at myself through the eyes of my mask, I found that *he* did indeed want something, need something. I became a 6-year-old at a zoo—he’s excited to see the tigers but worried that he can longer see his father in the crowd, caught between happiness and despair and his inability to know where he should belong or to control any of it. Then the entire class sat on one side of the room while, one by one, each of us stepped through a door with our mask on and got to live a little bit of their life in front of everybody. I stepped through and became my first-grade self, hoping he gets picked to read aloud, ready to share something for show and tell even if he has nothing in mind, jacked up on playing air guitar to the Beach Boys and never ever wanting to get down from that moment in front of everyone’s eyes. Is it embarrassing to admit these things to you now? As an adult, am I constantly worried about the level to which people can perceive that needy hyper boy in me? Yes. But the Mask let it all happen. The Mask was like a museum exhibit, or a trumpetist on-stage, or a song playing in a passing car—the “me” I was playing felt at a distance. The Mask put a piece of fiction between me and my classmates, and so it suddenly became possible to embody the things I am afraid of.

Shortly after making them, my class received the casting for our next production: Chekhov’s The Seagull. I was cast as a boy who is excited to share with everyone a play he wrote, who desperately needs his mother’s love, and who injures himself in the head after so much despair about his inability to know where he should belong or to control any of it. This was after I had already made the Mask, the Mask that I started making by focusing on the skull and following the bonk from nowhere. I didn’t know, but the Mask did.

Cornelius McMoyler is a second-year drama student